Climate change has made a profound impact on thousands of the plants and animal species. The threat triggered by the rapidly changing climate continues to reveal itself in new ways. But, the Penguin Post has learned that a new study by the British Antarctic Survey scientists, which was based on satellite observations of four emperor penguins, shows a ray of hope for the sea bird as they seem to be adapting themselves to the changing environment.

“This is a new breeding behavior we’re witnessing here,” said Peter Fretwell, a geographer with the British Antarctic Survey and lead study author. “This has totally taken us by surprise. We didn’t know they could go and breed up on the ice shelves,” Fretwell said.

The current study highlights the extraordinary change in the behavior of the emperor penguins that breed during the harsh Antarctic winter when the emperor penguins breed.

The satellite observation reveals that the penguin colonies drifted from their traditional breeding grounds to much thicker floating ice shelves that surround the continent. This change in the breeding behavior occurred when the sea ice formed later than usual.

Scientists at the Australian Antarctic Division and the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego in California also worked on the current study.

Fretwell explains that these birds breed on sea ice as this gives them an easy access to waters where they can forage for food. One such satellite observation of the penguins during 2008, 2009 and 2010 revealed that the annual sea ice was thick enough to maintain a colony of penguins. But in 2011 and 2012, it was surprising to see that sea ice did not form even a month after the breeding season started. At this point of tome the birds were seen going to the nearby floating ice shelf to raise their chicks.

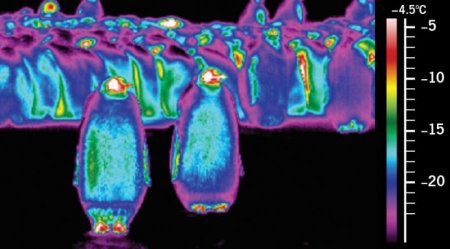

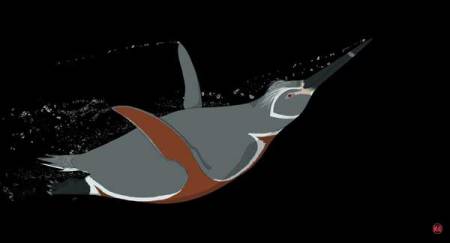

“What’s particularly surprising is that climbing up the sides of a floating ice shelf – which at this site can be up to 30 metres high – is a very difficult manoeuvre for emperor penguins. Whilst they are very agile swimmers they have often been thought of as clumsy out of the water,” he continues to say.

Since these birds heavily depend on sea ice for breeding purpose, they were listed as ‘near threatened’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s “red list” of endangered species.

This latest discovery may help scientists to frame the future of these scientists. The team plan on finding if other species are also adapting themselves to the changing environment conditions.